The Steinway Duo-Art Grand Piano, New York, Autumn 1914 onwards.

Introduction

The Aeolian Company was a relatively late entrant to the world of reproducing pianos, bringing the Duo-Art before the musical public in March 1914. By that

time the Welte-Mignon had been on sale for nine years, and various American manufacturers had already stepped into the market, such as the American Piano

Company, with its Stoddard-Ampico system, which is reputed to have been launched in 1911.

There would seem to be two reasons for this uncharacteristic tardiness on the part of Aeolian, namely an unsuccessful attempt to produce a synchronised phonograph and player piano, which occupied the Aeolian experimental department for many years, and an apparent belief that most music-lovers wanted to create their own interpretations on the pianola, rather than to listen passively to the performances of the great masters. It is perhaps significant that at the very outset, Aeolian sought to emphasise the triple nature of its new instrument, allowing for automatic performance, personal control of standard rolls, and the direct playing of the piano by hand. Such an instrument might more aptly have been called a Trio-Art, whereas the name Duo-Art would have ideally suited a combined phonograph and player piano.

Musical Example

As was the case with the Ampico for most of its existence, the Duo-Art recording machine did not record the pianist's dynamics automatically, and so the skill and experience of

the musical editors was paramount in determining how faithful a particular roll might be. This example was recorded by the young Chilean pianist, Rosita Renard, and published in the summer

of 1918. It is sometimes said that the highly edited Duo-Art rolls are more akin to portraits than to photographs, but a portrait can often be the more telling of the two.

Rosita Renard (1894-1949).

| SCHUMANN: Traumeswirren, Op. 12, no. 7, [2.2 Mb] Recorded by Rosita Renard - c. 1918, New York. |

This roll was played back on a Steinway Duo-Art grand in London, in December 2004.

The audio recording is the copyright of the Pianola Institute, 2006.

Mechanical Operation

Like the Themodist Pianola, the Duo-Art divided its playing mechanism into two halves, although the border from bass to treble

occurred between Eb and E above middle C, one note lower than on most other systems. The reasons for this difference were not documented at the time, but may have

been influenced by the phonograph/player piano project mentioned above, which adopted an 85-note piano as the standard, leaving the top three note tracks on

a normal 88-note roll to be used for synchronisation purposes. The centre of such a piano would fit more closely with the Duo-Art division.

In all normal reproducing pianos, an electric suction pump powers the playing mechanism, and supplies a sufficient level of suction for the maximum loudness needed by the piano. Proprietary dynamic control mechanisms reduce this suction level in various sophisticated ways, so that a wide variety of dynamic effects is possible. In the diagram below, air is evacuated from the Duo-Art playing mechanism (the pneumatic stack) through a pipe on the left, passing through various windways inside the expression box, and thence to an electric suction pump by means of the pipe at the top of the diagram. The layout below is not necessarily representative of an actual Duo-Art installation.

Part of the Dynamic Control Mechanism of the Duo-Art.

At the right, a perforated music roll passes over a tracker bar, which has holes in it connected via many small tubes to the individual note mechanisms of the instrument. At the left-hand edge of the music roll (and also at the right-hand, which is not shown), there are four special perforation positions which do not operate notes, but which instead allow atmospheric air to pass through elongated tracker bar holes, operating the valves to control one of two accordion pneumatics, as Aeolian called them.

Each accordion has four separate sections, which progressively double in span, from top to bottom. Thus, Duo-Art power 1, which is operated by the outermost dynamic coding perforation on the roll, causes the top section of the accordion to collapse, moving the left-hand end of the knife valve arm by 1/16th of an inch. Powers 2, 4 and 8, operated by adjacent perforations on the roll, collapse by 1/8th, 1/4 and 1/2 of an inch respectively. The animation shows each section of the accordion operating in succession, but in practice the four dynamic coding perforations on the roll can be combined, allowing for sixteen degrees of dynamic control.

An Overall Diagram of the Duo-Art Expression Mechanism.

The Accordion pulls on a small wooden arm which is connected, via a rotating rod, to one end of a knife valve inside the expression box. This valve slides over a port (usually a round hole in the case of the Duo-Art), and as it opens the port, it allows suction from the pump to enter the large regulator pneumatic. The pneumatic closes in opposition to a coil spring, and, by means of a rod attached to its inner surface, moves the other end of the knife valve until it also closes. Thus a state of equilibrium is reached, with the suction applied to the stack dependent mainly on the force exerted by the regulator spring, and also to some degree on the maximum level supplied by the pump.

This binary to analogue decoding was central to the Duo-Art, and in combination with separate Theme and Accompaniment regulators, switched by Themodist style perforations at the edges of the rolls, it had the potential for creating 32 different theoretical dynamic levels. In practice, since reproducing pianos do not operate at anything like the speed of computer systems, the 32 powers were more like miniature crescendos and decrescendos, in many cases dependent on the length of the perforations which operated them, and so the actual subtlety of dynamic shading was far greater than the theory might suggest. Besides, the response of the Duo-Art to its dynamic coding is modified by the number of notes being played, and even by any notes already played but held on by perforations that are still open. One should always remember that Duo-Art rolls were without exception edited on the pianos of the time, until they sounded right to the pianists and editors involved, and not to some theoretical standard, either of dynamics or piano tone, a point that both computer and player piano specialists should note well, before they embark on projects to bring the Duo-Art up to date.

The Duo-Art Recording Process

From the outset of the Duo-Art in 1914, and perhaps a little earlier, there was a piano roll recording studio at Aeolian Hall in New York, initially at the 42nd Street premises. The

first recording producers were W. Creary Woods and Arno Lachmund, who seem to have divided the work equally between them, if the handwritten notes on the surviving original rolls at the International

Piano Archive in Maryland are to be believed. Both men were trained musicians; Lachmund's father was a concert pianist and pupil of Liszt, and Woods went on to become the Principal of

the Delaware College of Music.

A similar studio was set up in London, England, at the end of 1919, and there the post of recording producer was taken by Reginald Reynolds, who had lately succeeded Easthope Martin as the British Aeolian Company's chief Pianolist. Laurence Crump, seconded from the player department of the Aeolian factory at Hayes, Middlesex, became the perforating machine engineer.

Unlike many other reproducing piano systems, the Duo-Art used a real-time perforator to produce an original roll as the artist played. This machine, patented by Edwin Votey, was capable of punching at around 3,600 perforation rows per minute, giving an accuracy, on this first roll, of 1/60th of a second. Dynamics were not recorded automatically, but were created on the roll as the artist played, in the earliest days by having a pianolist acting as a recording producer by pedalling a muted push-up Pianola, whose dynamic levels were translated into electrical signals relayed to the perforating machine. The Polish pianist, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, first recorded for the Duo-Art in 1915, and the controlling Pianola and its musical producer, William Creary Woods, can seen at a second recording piano in the background.

Ignacy Jan Paderewski recording for the Duo-Art, New York, June 1915.

During the course of an extended litigation process with one of its main competitors, Wilcox and White, which had patented a similar mechanism, Aeolian gradually replaced the controlling Pianola with a bureau-style cabinet that included two dial controls and other associated mechanisms, now operated mainly by the producer's hands rather than his feet. Around late 1919 a parallel Duo-Art recording studio was set up in London, with the pianolist, Reginald Reynolds, as the British recording producer, and in this photograph of Reynolds and Ferruccio Busoni, the British recording console and its dials can be clearly seen.Ferruccio Busoni recording for the Duo-Art, London, c. 1920.

Under the keys of each Duo-Art recording piano were a series of electrical contacts which ran through a cable to a separate room, where the rather noisy perforating machine was housed. Until the early 1920s, there were two contacts for each note, but half of these were subsequently removed in order to improve the touch of the piano action. According to Gordon Iles, who worked at Aeolian in London for a short period in the late 1920s, there were also two piano-type pedals attached to the recording console, and it seems likely that these were used in the early days, in conjunction with the extra note contacts, as a means of automatically punching Themodist perforations in synchronisation with any notes which the recording producer selected.

Teresa Carreņo recording for the Duo-Art, New York, 1914.

Once a Duo-Art original had been perforated, it was copied to a much longer stencil roll, on thicker paper, which was then used to produce several copies for editing purposes, known as trials. During the recording process, the original was pulled through on to a take-up spool, and so the paper speed slowly accelerated, and since the recording perforating machine punched at a regular 60 cycles per second, it can be clearly seen on all surviving recorded originals that the spacing between punch rows gradually increased. However, the trial rolls were produced on normal perforating machines, whose punch spacing was either 21 or 31.5 punches per inch, depending on the date of recording, and this lack of synchronisation introduced a certain "fuzziness" into the trials, just as the different line standards on US and European televisions used to mean that videotapes copied from one system to the other were not quite as clear as the originals. Much editing time was taken up with minute corrections of this nature, especially before 1923, when the finer perforation spacing was introduced. There is a surviving letter from Paderewski to the Aeolian Company, in which he asks them to tidy up some of his arpeggios, and in the past this has been wrongly attributed to a lack of precision on Paderewski's part.

Percy Grainger and W. Creary Woods editing a Duo-Art Music Roll - New York, c. 1915.

Whereas Welte in Germany did not invite pianists to assist with the editing of their own rolls, Aeolian made a feature of asking its well-known recording artists to help polish their performances. Percy Grainger observed that the Duo-Art represented him not as he actually played, but as he would like to have played. Harold Bauer and Rudolph Ganz gave extended press interviews on the subject of piano roll editing, which Aeolian then used in its advertising for the new instrument.

An Impression of Rudolph Ganz and an Unknown Editor working on Duo-Art Rolls -

New York, 1916.

At the end of the editing process, the final trial was approved and signed by the pianist, and became a pattern, to be used as a proofing copy in the manufacture of the roll for commercial sale. Of course, all corrections to a trial had to be copied across to its associated stencil, since this was the style of master roll used on the production perforating machines.

Duo-Art roll speeds vary from about 50 to 120, being 5 and 12 feet per minute respectively at the start of the roll, though mostly they keep to within a range of 60 to 90. As a rough guide, a roll speed of 80, with a perforation spacing of 31.5 rows per inch, gives an accuracy in time of about 1/50th of a second at the start of the roll.

Pianists and Repertoire

The haste with which the Aeolian Company introduced the Duo-Art in March 1914 is confirmed by the paucity of rolls in its first year. By the December of 1914 there were just one hundred

classical titles available, and the emphasis was on what might be termed "salon" music, rather than anything too demanding. There were also very few pianists of note in the earliest

catalogue, and at the outset Aeolian was reduced to converting Grieg's Autograph-Metrostyle roll of Papillon in order to associate the Duo-Art with at least one great composer. Many

of these early rolls were recorded by Felix Arndt, a composer of light music and member of the Aeolian Company's New York staff, who died in 1918 in the influenza epidemic. As might also

be expected from a system where the musicianship and experience of the recording producers played such an important part, these early rolls are not as musically successful as later Duo-Art

recordings.

An American Duo-Art Music Roll Catalogue - New York, 1927.

In the minds of the Aeolian Company's musical staff, the repertoire of the Duo-Art consisted of a number of distinct musical styles. The classical and light classical rolls were allocated a particular numbering system, while lighter music, songs and accompaniments each had their own area of the catalogue. Separate recordings were made in New York and London, with the numbers of the British Duo-Art series beginning with the letter 'O', presumably for 'Orchestrelle', the name of the Aeolian Company's British subsidiary at the time the Duo-Art was launched, and not the numeral '0', as is often wrongly assumed. However, some of the recordings made in London were in fact issued in the main American series, and probably edited in the USA as well.

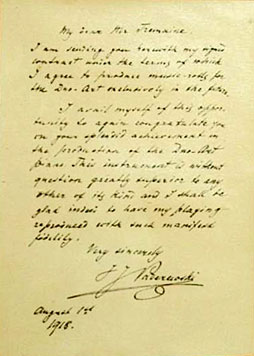

Paderewski Playing the Recording Piano at Aeolian Hall - New York, June 1915.

Slowly a number of better known pianists began to visit the Aeolian Company's studios, as they happened to be passing through New York. Teresa Carreņo, Ferruccio Busoni and Camille Saint-Saëns all made early American rolls on a non-exclusive basis. Then Percy Grainger moved to the USA in 1915, and since he was already in contact with the Aeolian Company in London, having arranged two folksongs directly for Pianola, his transition to exclusive Duo-Art recording was a very natural progression. Harold Bauer, an Englishman born in Kingston-upon-Thames, and Rudolph Ganz, from Switzerland, had similarly chosen America as their new home, and so were persuaded to become early entrants to the Duo-Art catalogue. Then, in 1918, Paderewski signed an exclusive contract with Aeolian, and gave the Company the opportunity of presenting its new reproducing piano as the world leader, rivalled only by Ampico, for which the slightly younger Rachmaninoff exclusively recorded. In fact Paderewski had made some trial recordings in the summer of 1915, as can be seen above, but he probably wanted to listen to the results before he made up his mind. The third most highly regarded pianist of the time, Josef Hofmann, also joined the ranks of Duo-Art artists around 1918, and so by 1920 Aeolian had created a substantial roster of pianists, and the decade of the roaring twenties saw the greatest flourishing of Duo-Art pianos and rolls.

Paderewski's Duo-Art Contract Letter - New York, August 1918.

By 1930, when serious Duo-Art recording all but stopped, there were about 2,000 rolls in the American classical series, and a roughly similar number of popular titles. The Aeolian Company in London recorded some 350 rolls, with a mostly classical bias, and it also perforated American series rolls for sale in Europe and the British Empire, including about a thousand popular titles for which it established its own numbering system. The style of dynamic coding used by Reginald Reynolds, the British Duo-Art recording producer, is quite different from the US pattern, and from the way that individual pianos respond to these coded perforations, one can assess that British Duo-Art pianos were generally set up to play differently (a little more loudly, and with a less quickly responsive sustaining pedal mechanism) from their American counterparts. During the 1930s, new popular rolls were still produced in the USA, though typically by a modified metronomic marking-up process, and not by recording at a piano. Indeed, Duo-Art dance rolls, and these include most of Gershwin's output, are not at all hand-played in the sense that they might actually represent what the performer played. Instead, musicians used a simple factory recording piano as a speedy way of notating their arrangements, and the resulting marked up rolls were used like written out musical manuscripts, as a basis for creating metronomic arrangements which would play consistently for singing and dancing.

Duo-Art Instruments

From the launch in March 1914, Duo-Art mechanisms were installed into Steinway upright pianos, and demonstrations were held in the Steinway salon at Aeolian Hall, New York. Whereas advertisements for

the Pianola and Pianola Piano had shown music lovers as active contributors to their own enjoyment, the new style of Duo-Art advertising sought to represent a couple, or a family in

deeply pensive mood, brought on by the acquistion of a new Duo-Art Pianola.

From an Advertisement for the Duo-Art Pianola - New York Times, March 1914.

Although the Duo-Art was launched by means of upright Pianola Pianos, it took only six months or so for Aeolian to have grands on sale as well. Like the original Welte, but unlike the Ampico and Welte Licensee, the grand pianos house the roll spoolbox in a compartment above the keyboard. The earliest Steinway Duo-Art grand piano known to have survived is no. 168475, made in about September 1914, and the top of the spoolbox can be seen over the keyboard fall.

Early Steinway Duo-Art Grand Piano, no. 168475 - New York, 1914.

By 1915, Weber Duo-Art pianos were also available, and the range gradually spread to include Steck and Aeolian in the USA and Britain, Gabriel Gaveau in France, and Ibach in Germany. Art cased instruments, with ornate and expensive decoration, were especially popular in America, and many attractive designs were created and manufactured at the Aeolian Company's factories. The following example shows a Weber Duo-Art grand piano with a lacquered Chinese Chippendale case.

Weber Chippendale Duo-Art Grand Piano - New York, 1927.

South America was fertile ground for exports, and there were strong Aeolian agencies in all the major countries. Alfredo Molina, President of El Salvador, owned a Weber Duo-Art upright, and is seen here in the early part of 1925, listening with rapt attention to his newly acquired treasure. One may note that the Metrostyle pointer, utterly redundant in the case of Duo-Art rolls, is nevertheless standing to attention at the front of the spoolbox!

The President of El Salvador and his Weber Duo-Art - San Salvador, Winter 1925.

(Photo: William Knightley)

Most of the grand pianos used for the Duo-Art were of small or medium size, but there were nevertheless a few concert instruments as well. In the late 1920s, Duo-Art mechanisms were installed into a small number of Steinway 'D' grand pianos, but for its own concert purposes the Aeolian Company built a series of Weber 9-foot grands around 1917. At least two of these have survived, one facilitating the return in 1985 of the late Rudolph Ganz to Symphony Hall, Chicago, where he appeared as posthumous soloist in the Liszt Eb Piano Concerto, with the Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra.

Orcenith Smith conducts Rudolph Ganz - Chicago, 28 April 1985.

Another Duo-Art concert grand belonged to Queen Elizabeth of the Belgians, and was for many years to be found in the Royal Palace at Laeken, near Brussels. This instrument is now in private hands, and it formed part of the special exhibition of player pianos at the Musical Instrument Museum in Brussels in the summer of 2007. It is shown here in a photograph taken from an advertisement by the Aeolian Company in Paris, which appeared several times throughout the 1920s, in the fashionable magazine, l'Illustration.Queen Elizabeth's Weber Duo-Art Concert Grand - l'Illustration, December 1929.

The original purpose of these full-sized grand pianos was as a means of publicity, and memorable advertising was certainly one of the areas in which the Aeolian Company excelled. The auditorium in its Aeolian Hall at West 42nd Street in Manhattan was the permanent home of the New York Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Walter Damrosch, and in 1917 it arranged with the orchestra to stage a concert in which Harold Bauer played the Saint-Saëns Second Piano Concerto. However, while Harold Bauer's playing issued forth from the concert grand Duo-Art in New York, the pianist himself was in Chicago, having been replaced by his recorded music rolls. Such performances were subsequently organised from time to time by Aeolian and others, but the evening of Saturday 17 November, 1917, was the first complete concerto.Harold Bauer watches his ghost rehearsing with the NYSO - New York, November 1917.

In the 1920s, not everyone had access to an adequate electricity supply, and foot-operated Duo-Art pianos were manufactured to fill this gap. These were also less expensive, and controlled only the Accompaniment side of the dynamic mechanism automatically, leaving the operator to create a dynamic level for the Theme notes by means of the foot pedals. The Steck shown below was manufactured at the Aeolian Company's factory in Hayes, Middlesex, close to the present-day location of Heathrow airport.

Steck Foot-Operated Duo-Art Upright Piano - London, August 1922.

Towards the end of the Duo-Art period, in the very late twenties and early thirties, a number of innovations were brought in, partly to help keep the market going, and partly as a result of new technology. The Concertola Duo-Art console allowed a quantity of rolls to be pre-loaded on to multiple spools, and then played in any order by means of a remote control device. In some late Duo-Art pianos, the familiar accordion pneumatic was modified so that it opened radially, like a book, and not longitudinally, as had previously been the case.

In 1932, the Aeolian Company effectively took over its main competitor, the American Piano Corporation, in an unequal merger in which Aeolian was the dominant partner. Many retail and manufacturing properties were sold off, and piano and roll manufacture was transferred to the former Ampico factory at East Rochester, New York. Ironically, the retention of the Ampico workforce and design team meant that Ampico features predominated in 1930s instruments, even though the major capital of the company had come from Aeolian sources. For example, late Duo-Art grand pianos were manufactured with the rolls placed in a drawer mechanism under the keyboard, as had always been the case with Ampico grands, and by means of a larger take-up spool and electric roll drive, both based on the Ampico 'B' design, it became possible to play much longer Duo-Art rolls.

The Aeolian American Factory - East Rochester, New York, April 1985.

But these novelties were not ever widespread, and the 1930s saw the gradual decline of the Duo-Art, as indeed of all other reproducing pianos. The recording studio in New York was closed, and in the end rolls were simply marked up by hand, mostly by Frank Milne, a Scotsman who had emigrated to the USA early in the century, and who ended up in charge of the musical side of roll production at the East Rochester factory. Of course, the manufacture of normal pianos continued apace, and only in April 1985 was the workforce finally laid off. The two gentlemen in the photograph above are George and Elmer Brooks, who between them ran the factory for many years.

The AudioGraphic Project

As the decade of the 1920s progressed, all piano companies must have gone through relatively hard times, and Aeolian encountered particular difficulties as a result of the British

subsidiary losing a very substantial amount of money around 1923. Rumour has it that the deputy works manager at the Company's factory in Hayes, Middlesex, was misappropriating whole

bargeloads of expensive timber and selling them off on the side. Whatever the case, Aeolian made strenuous efforts to keep its piano and pianola sales buoyant, and one of the ways it

chose to do this was to concentrate on the educational uses of the Duo-Art.

For many years, song rolls had been produced by various companies, with the lyric of a ballad printed at the treble side of a music roll, so that the assembled company gathered round the pianola would find it easier to sing along with the music. This was an early form of what we would now call Karaoke, and the rolls sometimes included simple illustrations.

Excerpt from a Nursery Rhyme Song Roll - Aeolian Company, London, 1920s.

In the mid-1920s, Percy Scholes, a well-known British musical critic and author, had the idea of extending the printed material on roll to include descriptions of the music and explanatory notes. Scholes persuaded George W.F. Reed of the Aeolian Company in London to present the idea to the parent company in the USA. An initial set of educational rolls was produced in England in 1925, and Scholes gave a series of musical lectures for children, at Aeolian Hall in New Bond Street, broadcast by the BBC and preserved in his book, The Appreciation of Music by Means of the Pianola and Duo-Art. This roll-based activity soon led to the publication of a full series of AudioGraphic rolls, as they came to be known, and a grand banquet was held in 1926 to launch the project publicly. Many musical writers and academic specialists were invited to contribute programme notes, which were printed at the start of each roll, and a series of artists was commissioned to produce woodcuts for the accompanying illustrations. Photographs were also included on the rolls, especially of composers and pianists.

The Banquet to Launch the Audiographic Project - London, Prince's Galleries,

24 September 1926.

The 1926 AudioGraphic Banquet had a guest list that brought together almost the entire British musical establishment, liberally augmented by European musicologists and American pianomakers, and interleaving a representative selection of the Aeolian Company's British and Continental staff. Luckily for us, a copy of the full-plate photograph taken during the course of the evening was preserved in Edwin Votey's private papers, together with the identities of those placed at the top table. The photograph can be seen above, albeit at very small scale, and since it appears nowhere else on the internet, it would certainly be worth including a number of snapshots of interesting areas of the festivities, and so in due course we propose to devote a separate page to this unique event. For the moment we have highlighted one particular selection of guests, at the left-hand end of the top table.

The two main instigators of the project are at the centre of this small group: George Reed, who is standing third from the left, and Percy Scholes, who is sixth. The others standing are Ernest Newman, Jean Chantavoine, Isidor Philipp and Lodewijk Martelmans, all musicians or musical writers, and at the right Sir Humphrey Milford, director of the Oxford University Press. Seated in front of Milford one can make out Percy Pitt, Director of Music of the British Broadcasting Company, in conversation with a woman whose face is unfortunately hidden, but who must certainly have been the concert pianist, Myra Hess, judging by the centre-parted hairstyle, and also from the fact that Ms Hess performed a duo with herself during the course of the evening, accompanying on a second piano her own recording of the Grieg Piano Concerto (First Movement), on Duo-Art roll.

George Reed and Percy Scholes, AudioGraphic Banquet - London, 1926.

It would take a complete website to document all the AudioGraphic rolls in detail, and it makes more sense on this general Duo-Art page to concentrate on one typical roll. Most of the rolls were published in two editions, Duo-Art and Pianola, with consecutive catalogue numbers. Rolls D-717 and D-718, published in September 1928, were a Children's Centenary Roll of Franz Schubert, who died in 1828. Virtually the only difference between the two rolls was the inclusion or omission of the automatic Duo-Art dynamic coding. Although many different musicians contributed programme notes for the rolls, Percy Scholes himself chose to address the children on this Schubert issue, and his natural good humour and wit are readily apparent.

Schubert Centenary Roll: Leader - London, September 1928.

The roll leader typically lists the pianists and musical scholars who had contributed to the AudioGraphic series, including the members of a number of international committees brought together for the purpose. In Britain, the Honorary Advisory Committee on the Educational Use of Piano Player Rolls was already in existence, and consisted of Sir Alexander Mackenzie, formerly Principal of the Royal Academy of Music, Dr J. B. McEwen, his successor, Sir Hugh Allen, Director of the Royal College of Music, Sir Landon Ronald, Principal of the Guildhall School of Music, Sir Henry Wood, Conductor of the Queen's Hall Orchestra, Prof. C.H. Kitson, Professor of Music at the University of Durham, Robin Legge, Music Critic of the Daily Telegraph, and J. Aikman Forsyth, Committee Secretary. Similar committees had been founded in France, Germany, Spain, Belgium, the USA and the Argentine. Although these gatherings of the great and the good were formed mainly in order to give the AudioGraphic series a certain international standing, one should not forget that the important musicians of the day were quite genuinely enthusiastic towards the player piano as an educational device.

Schubert Centenary Roll: Introduction to Military March, played by Bauer and Gabrilowitsch.

After a number of titles and printed introductions, the music on the roll begins with an abbreviated performance of Schubert's Marche Militaire, played by Harold Bauer and Ossip Gabrilowitsch. Since the roll being used for these illustrations is the Pianola version, there is no Duo-Art dynamic coding, but instead, instructions for expression are given to the pianolist. Coloured lines mark out the start of each bar, and delineate the various musical themes.

Schubert Centenary Roll: Beginning of Military March, played by Bauer and Gabrilowitsch.

On the right of the roll, a series of very small perforations can be seen, punched at the start of every bar, and used to trigger a special machine at the roll factory, patented by Reginald Reynolds, which printed blue bar lines throughout the roll, very helpful to the pianolist, and also useful to those following the music with a printed score.

Schubert Centenary Roll: Woodcut of the Young Schubert in the School Orchestra.

Amongst further performances of Schubert's piano music by Paderewski, Ignaz Friedman and Alfred Cortot, there are many woodcut illustrations of Schubert's life, and descriptions which set his music in context, all directed towards the younger listener, since this is designed as a Children's Roll. Finally, a short quiz tests the young listeners to find out how much they have learned, and the Oxford University Press takes the opportunity to remind parents of the three recently published Books of the Great Musicians.

Schubert Centenary Roll: Quiz, and Announcement of the Books of the Great Musicians.

A separate AudioGraphic series of rolls was published in the USA, supervised by the musical educator, Charles Farnsworth, but despite the prodigious amount of work involved in the design and production of these attractive rolls, they came too late in the history of the reproducing piano to have more than a transitory effect. Significant collections of rolls were donated to various educational establishments, including the Royal Academy of Music in London, and we are lucky that more or less complete sets of both the British and American AudioGraphic rolls were deposited at the Library of Congress in Washington.

The Duo-Art in Perspective

Of all the commonly found reproducing pianos, the Ampico copes best with a lack of regulation. When such pianos were initially re-discovered in the 1950s and 1960s, therefore, the Ampico tended to play

better than the rest, and this often led to its being unfairly regarded as the best system. In truth, however, all reproducing pianos have their advantages and disadvantages, and a really well-adjusted

Duo-Art is the match of any Ampico. But the fine musical adjustment of a reproducing piano is the least understood art in the player piano world, and one only has to listen to many

widely available CDs and LPs to be uncomfortably aware of this. It may well be that, even in the 1920s, many pianos were sold that did not live up to the musical potential of the best

rolls. The British Aeolian Company's Duo-Arts responded somewhat differently to the dynamic coding than did their American counterparts. W. Creary Woods, in charge of the musical side

of Duo-Art recording in New York, was well aware of this, since he corresponded on the subject with Harold Bauer, who, as an international concert pianist, had detailed experience of the

pianos on both sides of the Atlantic. That these two experts should have known of the problem, and that it nevertheless persisted throughout the 1920s, shows that the Company which

manufactured the Duo-Art was not greatly influenced by the subtleties of interpretation. How much less likely are we, today, to find more than a tiny number of Duo-Arts in perfect condition!

The Duo-Art is above all a system which depends on the skill of its musical editors, since it never recorded dynamics automatically. Later rolls are therefore generally better than earlier ones, and this applies equally to London and to New York. The best rolls are stunningly lifelike - Percy Grainger playing Cyril Scott's Lotus Land, Paderewski in the wistful little Chopin Mazurka, Op. 17, No. 4, which is on our Aeolia 2002 webpage. And yet, it is a shared and instinctive perception of our Pianola Institute audiences that the Ampico appeals to our sense of excitement, the Duo-Art fascinates our intellect, but the Welte-Mignon touches our soul. The reasons for this will be explored in more detail on our Welte-Mignon page when it is written, but in the meantime we hope this discussion of the Duo-Art will whet the appetites of those who in the past have doubted the artistic validity of the reproducing piano, of whichever system.

If you have read all the way down to the bottom of this page, then congratulations to you, and you deserve a treat! Here is one of this writer's favourite Duo-Art rolls, Josef Hofmann playing one of his own compositions. A clever man, Hofmann; it is not always known that he was also a very fine engineer and inventor, with a patented design of automobile springs that was widely used in the United States during the 1920s.

Website Links and Other Sources of Information

Duo-Art Catalog - A downloadable catalogue of Duo-Art classical rolls in Adobe pdf format, from the Reproducing Piano Roll Foundation.

Duo-Art Technical Information - Commercially available Duo-Art technical literature, from John Tuttle's Player-Care website.

BluesTone Duo-Art Roll Catalog - Rob DeLand's catalogue of currently available Duo-Art copy rolls.

Charles Davis Smith - Duo-Art Piano Music, A Complete Classified Catalog, The Player Shop, Monrovia, CA, USA, 1987.

Duo-Art Piano Music, A Classified Catalog, Aeolian Company, New York, NY, USA, 1927.

Larry Sitsky - The Classical Reproducing Piano Roll, (2 Vols), Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, USA, 1990.

Percy A. Scholes - The Appreciation of Music by means of the "Pianola" & "Duo-Art", Oxford University Press, London, England, 1925.

NB: This is a very wide-ranging subject, so look at our links and bibliography pages as well.

Inclusion of a weblink does not necessarily imply that the Pianola Institute recommends the services concerned. There are many Duo-Art pianos still in use, and many active restorers and archives with their own commercial interests to promote.